When the Contactor Temporary Reduction in Entropy arrived in orbit around Relimeët, its members found themselves in intense debate over the proper location for their elevator. The environment faced them with extreme hostility. Two stable Coriolis storms slowly orbited the equator-spanning ocean of the planet, spinning off unpredictable eddies of smaller hurricanes and ruling out the establishment of a floating anchor. They found safe dry land no closer than 22° north in the form of a small island entirely inhabited by hominins and their ancestral structures. They could find no clear space for an anchor on the island, even if they could figure out a way to generate the ribbon to span the extra distance. A vote determined that the Contactor would send expeditions to start their work without the benefit of an elevator, using aerodynamic Messengers to search for a solution to the now prohibitive distance between Contactor and surface.

The expedition led by the oceanographer Mekzja Kefn sought a solution at the equator itself. Responsible for three other zoölogists, Mekzja constructed a submersible Messenger and they set about trying to find a way to build an anchored ribbon attached to a seamount that could withstand the storms.

They never found a suitable undersea location for the elevator. What they found though was more central to their purpose as a Contactor and as members of the Academy.

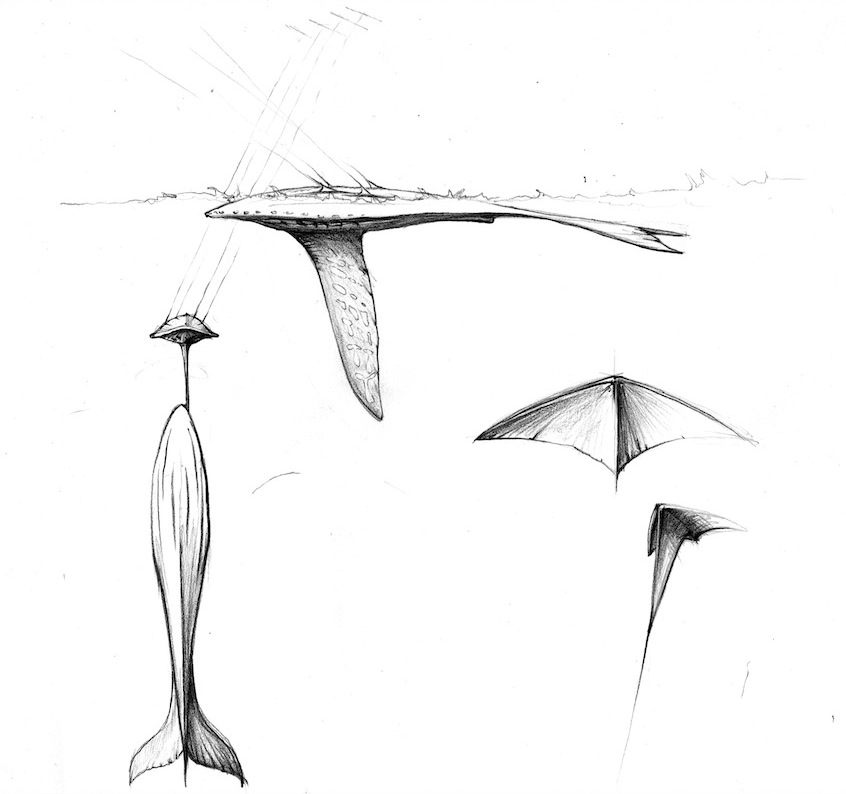

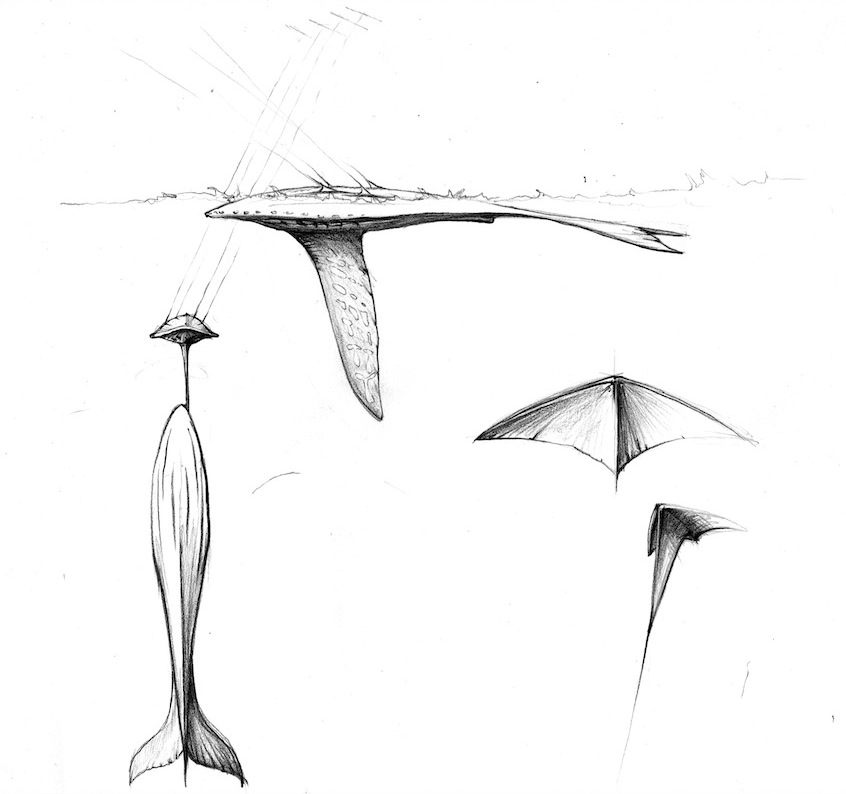

Traveling at the internal edges of the storms, they found gargantuan creatures, some 100 meters long, living at the surface of the ocean. They learned later that the Relimëetka called the creatures storm sailors.

Storm sailors live both by filtering nutrients and plankton from the ocean and by drawing kinetic energy from the storms. Their long, sleek, slightly flat bodies have two major features that distinguish them from other large sea creatures in Academic databases: a long, retractable keel on their ventral side and an array of “kites” that they retract into dorsal folds. At appropriate times, the sailor releases the kites into the storm, stretching out internal fibers that act as springs. The sailor then retracts the wings into the bodies of the kites, letting them fall and taking up the slack of the fibers with little effort. They repeat this process as often as they need to and use the energy they gain in this process to power both mechanical and metabolic processes.

The skin on their backs is tough, thick, and rubbery, capable of withstanding the lashings of the storms. Striations line their backs, housing the folded kites when diving.

Their keels have on their surfaces an array of bioluminescent features. Each individual’s array of lights appears unique. They use these features to communicate with other members of their school.

Their nervous systems are hugely redundant. Several redundant chemical information processing systems, similar to those found in simpler sea creatures in the oceans of Relimeët, seem to do long-term processing in parallel, communicating through a subcutaneous web of silicon strands. At points around the sailor’s midline, these strands expand into lens structures and protrude slightly through the skin around the equator of the creatures’ bodies, giving the creatures body-wide compound vision.

Through an yet-unknown process, the storm sailors can predict the eddy storms, choosing to follow the ones that best balance danger and nutrition. They communicate their predictions with each other with their bioluminescent keels, the light patterns directly interacting with each others’ brain networks. When in vicinity with each other, they furiously pass patterns back and forth, mimicking and modifying the patterns they see on the keels of the nearby individuals. They seem to converge on a common pattern, then place themselves in optimum configuration to benefit from the storms as they have predicted.

Mekjza Kefn has devoted his remaining time to interacting with these creatures. Though the team he led has largely disbanded to interact with the hominins living at the island, his partner Mna Kofa has decided to stay. They live together in their artificial sailor, complete with kites and luminescent panels, learning the language and cultures of these creatures.

Principles of creation

Often, when pressed to devise an alien on the spot, I’ve seen groups (including me) freeze, not wanting to overdefine things. I think this is part of our game culture, where you don’t want to step on others’ creative toes. Human Contact (because of Shock:s underlying Minutia rules) tell you when it’s time to listen, though, and I encourage you to use that to your advantage. Here are some steps to help you take the problem by the horns and create some unusual, plausible, and playable lifeforms for your colonies.

When I’m talking about life, I’m talking about two things, one literary and one biological. This article is to help you balance the two of these to help you make good science fiction.

The literary concern is whether these are creatures who are interesting from a point of view of society. They are features of the world that we recognize as sufficiently like people that they provide a moral question, simply by their presence. The Grid and the Minutia systems help this to happen. When in doubt, refer back to it.

The biological definition is a phenomenon that is a product of, and can participate in, evolution by the process of natural selection. Life as we largely experience it as 21st century real humans is largely a matter of extremely complex chemical and electrical processes that result in self-reproducing proteins. The things we see those proteins do are amazingly complex. Not only do their produce skin, scales, feathers and hair, but also through subtle variations in those protein reproduction processes develop pheremonal communication systems that allow them to build colonies in logs, systems of turning carbon dioxide into energy and releasing oxygen, religions, technologies, and philosophies.

Other life, given the broad array of environments in which natural selection and reproduction of slightly altered patterns can take place, might be truly mind-blowing. In addition to other possible forms of chemicals from our own carbon-based proteins, arsenic, silicon and sulphur might form the basis of other self-replicating chemicals.

But some might operate in completely alien environments other than the chemical realm. Pieces of computer code that can adopt each others’ variations when writing copies of themselves; Harmonic frequencies of the crystalline structures that vary themselves to benefit from to seismic events; Planetwide networks of simple life forms that predict and alter the weather according to their needs. How do these systems interact with a hominin presence?

Naturalism

Human Contact takes a Naturalist view of the universe. When we describe something, we describe the effect it has on our senses: what it looks, feels, smells (tastes? sounds?) like. It exists because the process of evolution has resulted in this particular phenotype that you’re looking at now. We define it by the characteristics that have helped its ancestors to reproduce. We know, of course, that they’re serving a purpose in our narrative, but the lens through which we look at it is a naturalist one.

A lot of adventure fiction doesn’t take that perspective, though. It cares that monsters are terrifying, perhaps, but it cares more about the impact it has on a character (and by extension, the reader). Attempts at describing a supernatural world in Naturalist terms yields questions about the buoyancy of dragons and the implausibility of interstellar species’ mating viability. The purpose of dragons in a story is to have something supernatural, intelligent, and malevolent. The purpose of Spock is to provide a metaphor for multiracial individuals in American society.

So, when we’re creating a creature from scratch, our tendency is to create something we need at the time, relying on either cliché or vagueness. Let’s talk instead about how to make something that you can look, feel, and taste. Something that belongs in its environment first — you can develop its metaphorical qualities later.

This branch of art is called speculative zoölogy. Let’s look at some of my favorite examples:

Æsthetics

The first thing you’ll notice about these is the consistency from one creature to the next. Real life is more complex than any art can hope to simulate of course; we have both starfish and birds here on Earth. But we also have sparrows, ostriches, penguins, kestrels, and a million kinds of finch. Our challenge is to find a balance between excess, dull similarity and total unfocused divergence.

When you want to make it seem like ecologies are neighboring, do the same thing that you do with dialects in Human Contact: change a subtle but noticeable thing or two here, leaving the rest and seeing what your new synthesis produces. Rather than starting from scratch every time, use the stuff you’ve already created.

On Earth, we might aesthetically divide our creatures into bilateral (insects, mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, cephalopods, etc.) and multilateral (starfish, jellyfish) symmetry. The bilaterally symmetrical particularly interest us, so we can divide those into tetrapods (fish, birds, mammals) and polypods (arthropods, mollusks).

If I needed to create a creature for Earth, I might say, “OK, there are a lot of polypods. A lot of of those live in the ocean, so I’ll take a nautilus, and I’ll give it symbiotic algae that live on its surface. They attach to this giant nautilus and absorb sunlight. The nautilus eats them and travels seasonally to the places where the algae are healthiest.”

Symmetry

Much of the process of evolution is about efficiency — the maximum use of available resources. Sometimes that means growing two or more parts the same way. In many animals, that means bilateral symmetry (one side of a being mirrors the other). In others, it means radial symmetry (similar structures all connected at a central point or branching (structures that are copies of the structures they’re attached to, which are copies of the structures they’re attached to). Such shapes form blossoms, spirals, and stars. These patterns are one of the things we recognize as features of life. While some nonliving phenomena like crystals and weather patterns have these characteristics, most nonliving phenomenal don’t, and by contrast, most living phenomena do.

Starting from a niche

But we can make more interesting things if we don’t have to start with Earth animals. To do that, we’ll have to come up with an environment. We’ll do this in much the same way we do with our hominins, without the assumption of basic human physiology.

- What environmental factors have shaped their bodies? We call a set of physical constraints on evolution a niche. Some fish live in salty water. Some in fresh. To maintain turgor pressure in their cells, very few can do both; when they do it requires a biochemical and physical change.

- What colors or patterns are their surface? Does it require protection from the sun? Camouflage? Bright colors and patterns to communicate?

- What holds the creature together and protects in from hostile elements? Skin? A shell? Hair? feathers? Leaves? A biopolymer made of chewed plants that hold stones in place?

- How big are they compared to the hominins of this colony and the Academics?

- How muscular, fat, and boney are they? Do they have tensor muscles like we do? Hydraulic compressor muscles like spiders? External sliding threads?

- How do humans interact with these creatures? Do they use them for food, drugs, labor? Do they live in symbiosis? Are they predated by them?

- If social, how do the creatures communicate? By sound? By vibrations in the ground? By patterns on feathers? By chemicals? By a naturally evolved radio?

If you make your ecosystem according to your Grid — according to your Shocks and Issues — then your creatures will, in some proportion, support those themes or add to a vivid background. There’s no reason to force them into allegory, so make them maximally plausible and you’ll find your way toward what they mean readily enough.

After all, we’re humans. We make metaphors out of everything we see.