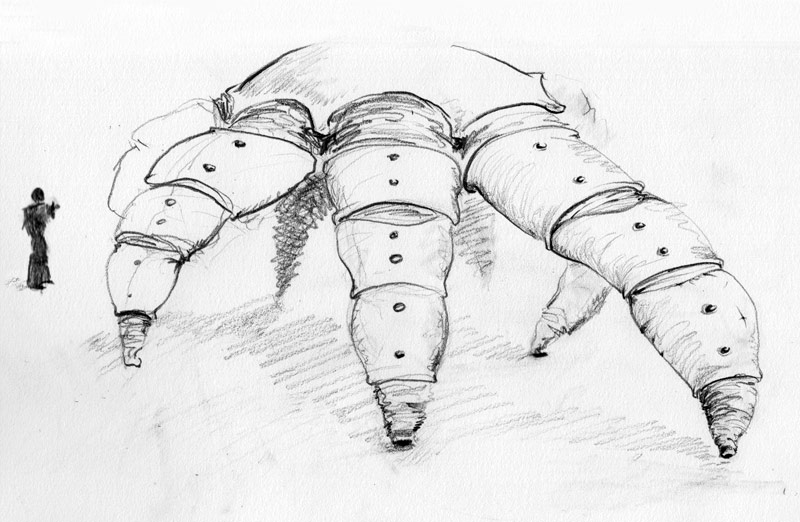

The Fibonacci geyland of Ashlesa 3.1 is a vast “grass”land of Monoforms that support the coboglobin-based ecosystem of Diforms, Triforms, Pentaforms, and Octoforms. This, the Titanic Pentaform, is the most massive Pentaform discovered to date.

Tag: Ashlesa

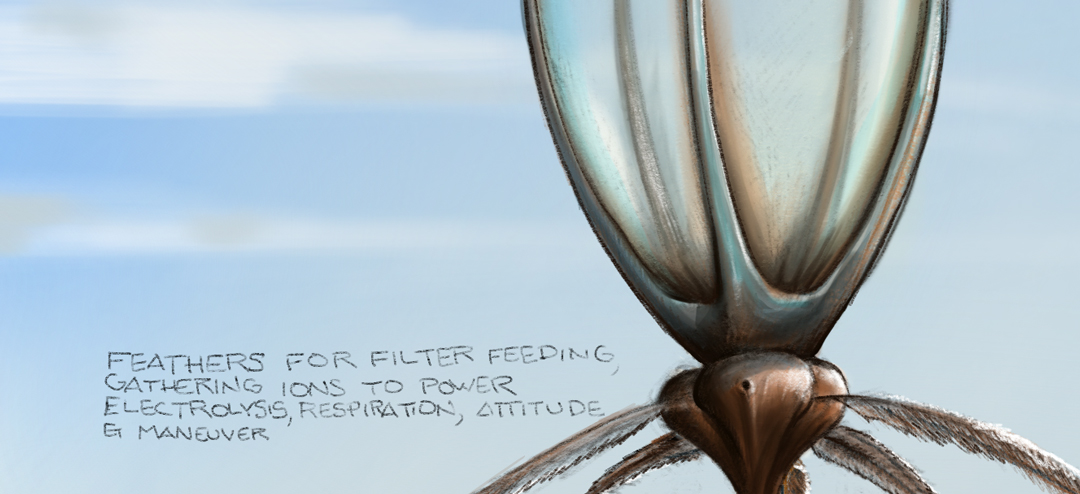

The Filter Feeding Aerial Pentaform of Ashlesa 5.2

Ashlesa 5.2 has a rich set of near-isolated ecosystems. Among the few entities that can cross the vast deserts of the planet are the flying Pentaforms, of which explorers have identified two species.

Where the other is an aerial predator, this one is a filter feeder, a solitary flyer.

Continue reading “The Filter Feeding Aerial Pentaform of Ashlesa 5.2”

Ashlesan Warrior of the Southern Heart, complete

The little guy’s complete!

Continue reading “Ashlesan Warrior of the Southern Heart, complete”

Ashlesan Warrior Sculpture, Painted

Painting is nearly done! You can see a spot I missed completely on the right knee, and there are a couple of spots that still need work, but the body’s just about done. Next come the banners, which will brighten the monochrome substantially. More pics under the cut!

Ashlesan Warrior sculpture

I’ve been working on this guy quite a bit. Materials have been about $25. No special tools, but I made some sculpting tools out of music wire and dowels. More pics below the cut!

Warrior of the Southern Heart Sculpture

I haven’t made any sculpture in years, and I’ve never used Sculpey to do anything but make little beads. So we’ll see how this goes. I’ve gotten a lot of help from the extraordinarily kind and knowledgeable artists over at the Concept Art fora.

Lots of pictures of this Warrior of the Southern Heart of Ashlesa 5.2, so look after the break. As with all art on the site from now on, you can click images to get a belargened slide show.

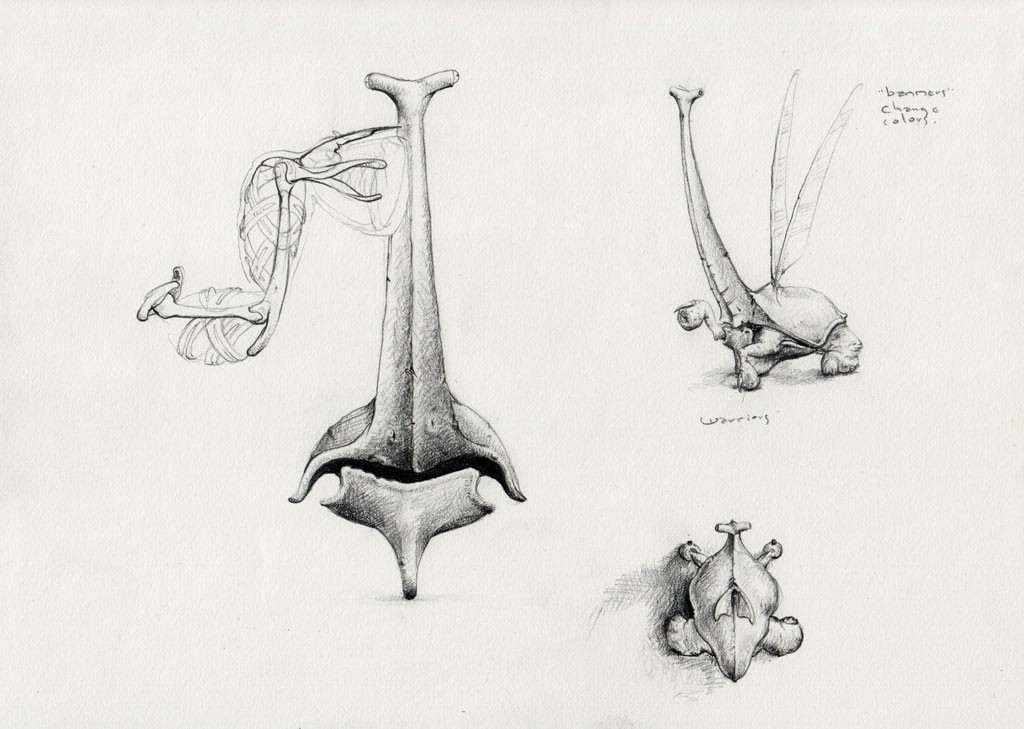

Warriors of the Southern Heart

In the geyland called the Southern Heart lives a species called “warriors” by the explorers who first discovered them. They’re herd animals, living among twenty or thirty of their kind. They’re about 1m tall, to the top of their banners and eyes and about half as long. Their feet each contain a circular mouth on the bottom, covered in raspy skin that they use to scrape minerals and microfauna off the ground. On the front of those feet single spikes. Their paired eyes are at the top of a tall tower at the front of their smooth, tortoise-like shells. Sprouting from their backs through a small hole in their carapaces are two tall feather-like banners in shifting, bright colors and patterns. Their hind legs are thick and strong, but the front ones are lithe and move in quick, snappy motions.

Warrior herds graze within eyesight of one another, no more than 12m away from each other. The twin banners on their backs are for herd communication. Each herd has a unique pattern that varies with context. The better the food, the broader the stripes, for instance, with herd members moving closer to individuals whose stripes indicate a better food source. They also sound the alarm, signaling predators and seeing other herds. The high eye towers allow them to see over other herd members while they graze, and quickly see changes in the environment and alert others to that change.

The muscles of the warriors, like those of most creatures of the Southern Heart, are hydraulic and work in compression, rather than the tension as most terran muscles do. Like many arthropods on Earth, they have very limited tensor muscles, gaining their real strength and speed from their hydraulic system.

When an individual warrior sees another herd, its banners suddenly change color into vibrant stripes that are clearly distinguishable from those of the other herd. They then charge into battle at a glacial pace, their thick hind legs pushing them forward and their front limbs working together to lift the keel of their shells off the ground. As they approach, the banners of the individuals change patterns subtly to indicate tactical openings they see. They coördinate themselves like this, inching themselves into position until they stand close enough to other individuals that they can strike with their barbed forelimbs. But this battle is not for territory or resources. The barb on the creatures’ forelimbs are injectors of spermlike structures, carrying the individual’s genes into the circulatory system of the struck individual. It also contains a hormone that causes the struck individual to stop fighting and signaling, recovering completely only well after the fight has ended.

The spermoforms are carried by the recipient’s circulatory system to an ovary, where they gestate for several days, eventually to be born in a 10cm sack, its eye tower collapsed along its back. The mother helps tear open the egg sac and the newborn climbs onto the mother’s back, where the eye tower erects over a few minutes. While on its mother’s back, it begins mimicking the coloration of the banners in its own herd. The shell hardens over a few days and the newborn begins grazing alongside other individuals. Over the course of a season, it will grow to full size, now part of its mother’s army.

If you have any questions about the warriors, the geyland of the Southern Heart, or anything else about Ashlesa, please put them in the comments and I’ll be sure to pass them on to the proper Ashlesologists.

Want to know more about Ashlesa? There are several articles on this blog. As exploration continues, more will be posted.

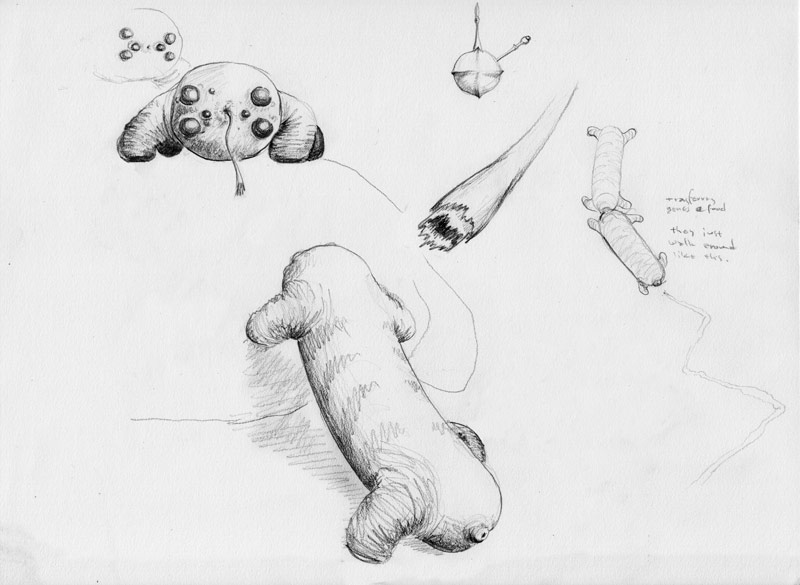

The Polar Piglets of the Boreal Geyland of Ashlesa

In the northernmost geyland of Ashlesa live the Polar Piglets. The 35 cm long, waddling creatures are highly social in nature, spending as much time as possible in close proximity to several other individuals.

They mineral-rich water flowing up from below forms large, bulging rocks wherever vents open to the surface. These rocks are filled with microfauna — there being no true “plants” on Ashlesa — that eat the inside of the rocks, expanding colonially and through the underground streams and rivers. They’re the primary food of the polar piglets, who look for the rare tiny holes in the rocks where the microfauna dig too far. When they see such a hole, they waddle up to it and insert their 20 cm prehensile radula, rasping the microfauna off the interior walls of the hollow rock.

Once the piglet has been satisfied, it stops completely digesting its food, forming it into little balls in a crop and mixing it with packets of its own genetic material.

When a piglet sees another up against a rock, it will amble up and attach itself by its soft mouth to the cloaca of the grazing individual. It will stimulate the grazing individual with its radula, receiving the balls of semi-digested food and genetic material. Chains are made this way as much as four individuals long, each receiving the passed-up food and genetic material of all the individuals ahead of it. Past four, there is little nutrition and the genes are too jumbled to be much use. The last in line lays eggs of all the combinations of genetic material, with each individual’s material being combined with the material of each and every of those behind it in all possible ways.

Consumptive and procreative purposes aside, the piglets spend much of their time so attached. They travel around in chains of two or three, and when groups meet another, they’ll often form rings and knots in an ecstatic, wiggling, chirping pile.

Do you have questions for the researchers on Ashlesa? Please ask them in the comments below.

Please keep comments polite and scientific. HAB members, this means you.

(please see the thread on the previous Ashlesa post for questions and answers there.)

An introduction to Ashlesa

When humans first orbited Ashlesa 5.2 (the second moon in orbit around the fifth “planet” — itself a brown dwarf — orbiting the star Ashlesa) , they were struck by its geology. A single vast plain, desert-like, with the occasional oasis dotting the landscape, broken only by chains of geysers, some thousands of miles across. Subterranean rivers ran under the hard crust, emerging only rarely. Life flourished both outside and in the geyser chains, but they seemed completely distinct. Not only was life in one of the “geylands” (as the explorers called them) different from that outside, it was distinct from every other geyland. They were each an entire closed ecosystem, biochemically (and in one case, physically) separated from the rest of the planet.

A team landing near the equator were met by titanic, 8-limbed, starfish-like creatures, slowly walking in a widely separated herd. Each “foot” was an obviously sensitive organ, feeling along, apparently sniffing and grazing on the thin scum that covers much of the broad plain. Its limbs were dotted with small, black, featureless eyes, largely facing up. The creatures, “Octoforms” as the explorers called them, completely ignored the human explorers.

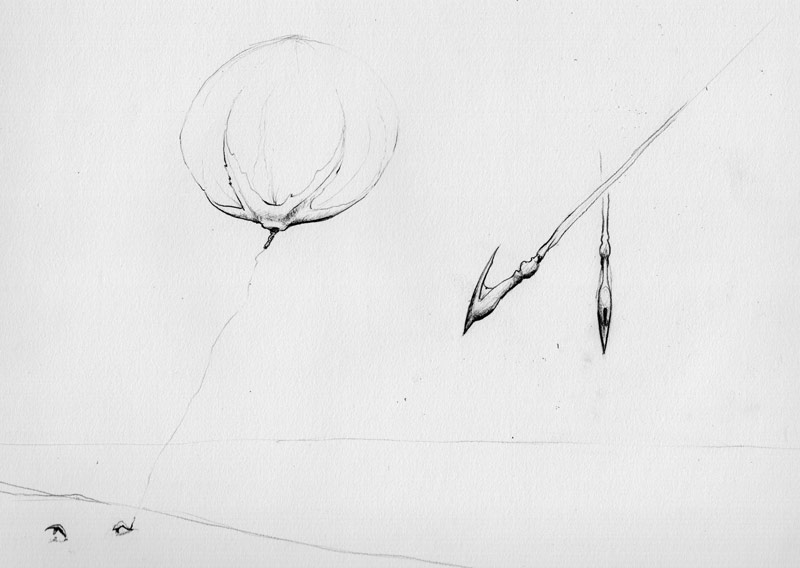

Landing near the Boreal geyland, the explorers discovered 40 cm wide, three-limbed creatures they called “triforms” happily grazing on some sort of biochemical sludge at the edges of the glacier. While observing them, the explorers were startled when a harpoon shot from the sky and speared one, followed by a crack like a gunshot. Floating silently in the air above the triforms, its shadow cast to the north of its prey, hovered a balloon. Five arms reached out and hugged the envelope. A small cloud of steam drifted away on the wind. The remains of the triform’s small herd had galloped away, turning like wheels, scattering like birds. The speared one struggled for mere seconds before it went completely slack.

The harpoon remained embedded in the creature and the ice below it for several minutes while the surveyors noticed that they prey was becoming a dry husk. After a half hour, there was so little of the creature that, when the zoölogists approached later, there was nothing but a dry skin on the ground.

The balloon had retracted its harpoon and was drifting away slowly, directing its flight subtly with small barks of fire from the appendage from which it had fired its harpoon. It drifted up and away until its form was no longer distinct. “It’s like lightning that wants to hit you,” said one awed researcher.

A boreal triform was discovered, partially eaten by some other animal. The team lost no time in dissecting the fresh specimen. It is completely symmetrical, each limb being a complete copy of the others. It is covered in a thick skin that responds to electrical pulses, itself a fine muscle. Underneath the skin are many thick bands of heavier muscle tissue, supported by a fibrous, almost plastic quill running the length of each limb. This particular species has soft, fine “fingers” along each limb, each with a small orifice.

At the base of each limb are what appear to be several clusters of nerve-like fibers. Experiments with living triforms — and indeed, every other planar form of life on Ashlesa — shows that the distal nerve clusters control reflexes and autonomic activity of the limb. The most proximal body, on the other hand, seems to be involved in communication with the other limbs. With their simple eyes, this is the only way the creatures can assemble complex vision. As it is the largest nervous body, this is apparently a challenging task.

Coming up:

Polar Piglets. Warriors of the Southern Heart. The closest thing to a “plant” on Ashlesa.

If you have questions about life on Ashlesa, please ask in the comments and I’ll pass them on to researchers in the appropriate field.