The Gulabadam sat at the newborn campfire ruminating, his prodigious jaw grinding slowly at the plain, salted barley flatbread that he found so delicious. His tail wrapped around his waist, sitting in his lap like a pet, and his huge, bovine eyes glittered in the firelight and dawn gloaming.

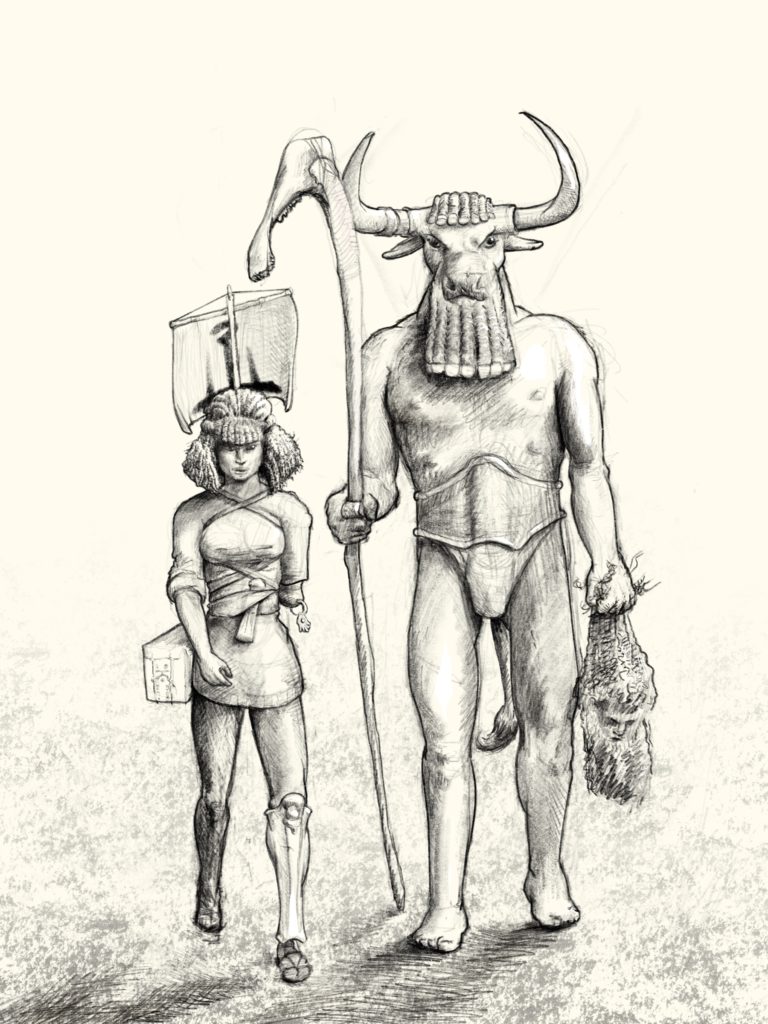

Even sitting, he was as tall as his standing companion, a slight woman called Galil, who dexterously removed her writing implements from a thigh-sized, leather-topped box with her one good hand and the stump that had once been her left forearm, pierced with a ring from which hung a tiny, wrought-silver hand. She sat, crossing her legs, and removed the bronze greave and sandal that formed her left calf. The sandal flopped, lifeless, to the sand before her, and she lifted it reverently with her right hand aided by the stump of her left, putting it in the box as though it were a sleeping child. She repeated this with the greave, tying the box’s leather thongs to keep the lid tight. With her right hand, she massaged the stump where the greave had formed her knee as though massaging a tired calf from the night’s long walk.

The Gulabadam handed her a piece of dry flatbread without a word. “Thank you,” she said flatly, removing a small piece of cured meat from a fold in her clothes. Combining the two, she joined the Gulabadam in silent rumination. The Gulabadam handed her the remains of the skin of water and she accepted it, drinking in the cold of the night that it had taken on while they had walked in cool, moonlit darkness.

“We have to find water tomorrow,” said Galil, returning the near-empty skin.

The Gulabadam nodded his expanse of head, and then emphasized in his deep, soft baritone, “Yes.” Galil felt his voice in her chest, despite the soft tone. The Gulabadam could empty ten skins of water or wine and could consume fifty flatbreads in a day. Travel with him had challenged them both, but the warmth and shelter he provided with his enormous body had protected her well.

The Gulabadam’s inhalation sounded like the rush of a waterfall. He spoke with slow deliberation. “I am leery of King-Father Abzkur’s spies. They had no reason to be in the village Daleb but to seek us. Crushing them will not be enough. I think they know that we travel to Bashab. We may find that his guard there lies in wait.”

Galil nodded. “I have hidden you for three years, Gulabadam, child of the river of Zush and the Queen Anash. It may be time to face those who have pursued us with such jealous zeal. They no doubt fear spilling your blood lest Abzkur lose his protection. But they know that you will defend me, and will use me as a weapon against you.”

The Gulabadam made a sound like the wind rushing through a deep wadi. He looked away. “I will protect you,” he said.

“And I, you,” said Galil, her eyes unwaveringly seeking his. Finally, he looked back. Each of his eyes was the size of her right fist, and as brown, shining like an agate through the fine white fur that covered his skin. Scars dotted his face. Scars from arrows, from slingstone, from khopesh, from dagger, from spear. His right horn — adorned with the armlet of Prince Mushul, whose love for the Gulabadam caused him to betray his own father unto his own demise — lacked its point. His black nose, now dry in the desert heat, bore a scar from Hafyush, who coveted his skull for a standard to bring honor to her tribe, and to gain her proper place at the side of her father and chief. Instead, she had inherited the tribe when the Gulabadam had struck the father from his saddle with the very skull he had coveted.

His might — or the cunning of Galil — had ensured that each wound had scarred, rather than exhausting his life. She had pledged to the river Zush; and to Zoram, the perfect bull, betrothed of the river who wished to meet his destiny in her; and to the Queen of Cattle Anash whose husband was Abzkur, but whose lover was the bull, that she would help him achieve his great destiny.

And now, only five years later, he who stood the height of two men; he, who had defeated Mumadak, first son of Mumadam, and returned to his head to his father in return for an honor-bound promise to turn over his other children to the Namedealer Dareb.

The first rays of the desert sun cracked over the horizon as the two finished erecting their simple tent, little more than an abaya draped over the Gulabadam’s jawbone-topped staff, angled to protect them from the desert sun while they slept.

They awoke as the sun began to recede. The hard sand was still warm, but the air felt cool on Galil’s skin as it ruffled her layers of desert clothing that had once been white, dyed with indigo in the Desertman fashion, but was now the uniform grey-brown of the sand around them. As the Gulabadam’s bulk lifted itself from slumber, he snorted, blowing dust from his nostrils. He rose, and then, lifting his jawbone-topped staff they used as a tent pole, pulled up the simple tent and wrapped it around his body as protection from the everpresent sand. Soon, the air would be cold as the sky — now the color of the hidden indigo of the abaya — darkened.

The Gulabadam held out the waterskin to Galil. She shook her head. “Drink,” she said.

“So little will do nothing for me. But for you, it is plenty.”

She tried to refuse, but found her thirst as compelling as his reason. “Thank you,” she said, and she drained the last of the skin.

Galil looked at the sky to check the location of the stars. She pointed across the desert. “Bashab lies in that direction,” she said.

The Gulabadam nodded his broad head, and they began to walk.

They could smell water long before the river glinted in the moonlight. Their skin drank in the moisture. When they reached softer ground, dotted with leafy plants, they did not speed up, but the footsteps of both rose with greater alacrity. Finally, they could smell the city from downstream, the shit and garlic, the smell of dead animals mixed with the smells of beer and bread. Spices and oils wafted to them along with smells of poverty and desperation.

When they reached the water, they did not disrobe, but instead strode into the cool water, feeling the dust detach itself from their skin and clothes, falling away as thick scales of mud. Both drank deep when they were far enough into the river to do so. No words crossed their lips while they refreshed themselves.

An hour later, the sky was turning pale in the East. Galil and the Gulabadam sat on the shore, now naked. Galil gently worked to return the curls to her matted hair with a ten-toothed comb in her right hand. At her feet lay the picked skeleton of a small fish that had met its demise at her hand. The Gulabadam lay on the shore staring upward at the dimming stars, blissfully chewing a fistful of grass gathered from the edge of the river.

Their clothes hung on a snag and, when dawn arrived and the smells of the city Bashab again began to intensify, they dressed themselves in clothes that again had the color of flax and indigo. The Gulabadam shined the armlet on his horn while Galil put on the sandal and greave that were her left leg.

Without a word, they strode together toward the demise of the mighty guard of Father-King Abzkur.