The storm howls through the bamboo for days, bending them until the largest, toughest ones burst, coughing sharp needles into the air. We use our squirrel oil sparingly, but it is dark inside the libarrow and we must see to read. While one of us writes, another reads from the same lamp to the too-many occupants. We read to them the tales of Allis each day, who chases rabbits and grows large and small. Lord Golden laughs at the nurse who bellows and shakes the baby and again at how she outwits the cards — which we explain to Lord Golden are leaves with writing and pictures on them, like books, but unbound so you don’t know what order they come in. He wants to know where this Wonderland is so that he can see its leaf people, and asks if Allis is still alive, that she sounds like a powerful shaman who might tell his future.

Continue reading “The Tale of Everyone Loves Him”Tag: Libarrians

The Shelter of the Libarrow

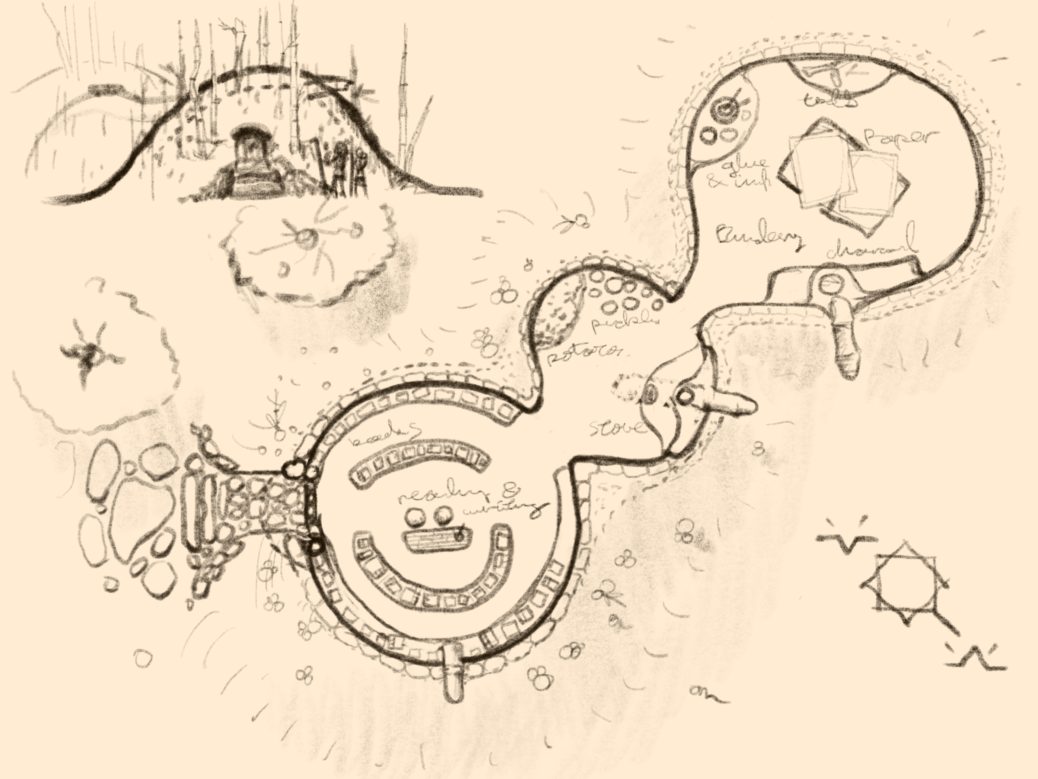

As we duck through the door into the Grand Hall of the Libarrow, I tense. I smell smoke. But when Jerone and I take a quick survey, we see that the room has barely been touched. The occulus splashes light in, dappling the low tables under which rest all the books we’ve written next to those of our ancestors and their ancestors. Since last we were here, someone has finished and bound the previous chronicle and begun a new one, its leaves loosely tied so we can write about the year and read about theirs, and placed it at the appropriate place.

Continue reading “The Shelter of the Libarrow”Meeting Lord Golden

First through the door of the Libarrow comes the toughguy who went in, carrying his club. Then comes he who I assume is the Lord, his face painted with the thunderbolt and Radiactive. He wears rings of glass on each finger but the pointer of his right hand, which carries a ring of gold. The finger on which it rides is short and scarred. He wears a codpiece made of carved wood that looks like a deer dick. He carries a club that I hope to never see used in anger — long as he is tall, headed with fine-ground stone, hafted with delicately graven Maina wood. It looks like it has pictures in relief on it. I would love to take the time to record them. They’re in a spiral, so they’re probably a story. The lines on his face tell me has lived perhaps 100 hurricanes.

Continue reading “Meeting Lord Golden”Lord Golden

Lord Golden is a character the Libarrian Tribe meet at the Harford Libarrow. He’s…not a great guy.

Continue reading “Lord Golden”A Libarrian Tribe Tries to Leave Conatikut

Hurricane Season begins abruptly this year, just as we approach the Harford Libarrow on our way to the Conference at Abani Libarrow. Our shamans haven’t yet met this year, so we don’t know the name of this storm.

We expect some storms, sure, but we checked the stars in the clear air last night and the time of year isn’t right. Too close to the Solstice for more than normal thunderstorms. Not the ones like this bruised blue-gray cliff of clouds that approaches from south of west.

A hill of bamboo forest marks the spot of the Harford Libarrow, ringed by peach trees — a symbol every tribe knows — and we can tell that others are already sheltering there from the hurried tracks they’d left not two days before. Enough footprints to be a small band, maybe a dozen people, so there should be plenty of room for all in the Libarrow, with its well and potatoes and just maybe some of last year’s pickled peaches, even if there’s no time to pick them this year. But Nisha points out something that gives us pause despite the approaching storm: wheel ruts to one side. Wheels are part of the Hoarder religion. They carry so much with them that they think it’s better to wish for roads than to carry less.

I go with Nisha to get Jerone so we can confer about what to do.

“We have to get into the Libarrow,” pleads Jerone, their broad, smooth features knotting in concern as the wall of wind approaches. “And we can’t let Hoarders rampage around a Libarrow without assistance.”

Our family begins to accumulate around us to listen to the conversation.

“Yeh,” I concur, “But if they’re planning on hoarding here, they’re at least as dangerous as Nameless, as she approaches from south of west.”

Mika addresses me, “Benna, Hoarders leave survivors. Hurricanes don’t.

Jerone answers, “Yeh, I think we have to go in and be prepared for the danger they bring.”

“Yes,” I agree.

“Yes,” agrees Jerone.

The rest of the family has arrived. In a few minutes, they confer on the conversation, repeating exactly until everyone has heard. They’re concerned about the Hoarders, but not as concerned as they are about Nameless.

We approach the hard bamboo door of the Libarrow, engraved deeply into its wood with flint chisel, the grooves repainted each year while we rest there, the words, “Enter, Those who Learn; Disperse, Those who Teach.”

The Libarrian Tribe

It had been hard, our elders say, pulling out of the Contraction. The Hoarder Peoples’ stories say we are still in it, that we haven’t actually reached the Sustain as we hope, and never would. We, the Libarrian tribes, stay away from them. We carry the healing words for traumatic, intergenerational memories of starvation, of skies choked with smog, of tornadoes and hurricanes chained one to the next like a necklace cinched so tight it’s left a gash in the soft neck of the world.

But now the world is more balanced than the world in our stories. The tornadoes and hurricanes have seasons, and between them things are different. Summer ends with hurricane season, and it lasts til Spring. We know it. We show our kids the way our parents showed us: four parents to each child, teaching to read, to write, to watch, and to teach.

We tend our raycats and teach our kids how to feed them so they’ll eat rats and bugs out of our food stores, and we teach them the rhymes about reading the colors of a raycat’s pelt, even if we’ve never had to do it, singing it to them as they grew up, teaching the teenagers to sing it to babies when they are old enough to take care of them.

Hush little baby, run away

If a raycat’s changed today

Care for family, care for you

Go back when the raycat’s blue

They shout, “Run like a raycat’s blue!” to get others to play with them, and whoever shouts it is the blue raycat, and they try to catch everyone before each of them got back to their starting stone. If they get caught, the kids say they’re “left behind.”

No one wants to be left behind.

And we say, “The sky looks raycat blue” when a storm threatens.

And we teach them to read and write and to tend the Libarrows at beautiful spots on our travels between hurricane season and dust season, so others could find them and learn from them, even if we are gone. We keep and repair and construct books about how to read; books that show you the names of the leaves and animals and weather that everyone knows; and books stories: how Prometheus found aluminum and smelted it and left it all over the world so now we can use it for all sorts of things, like knives and jewelry and joining bamboo and turning its leaves to paper to bind books. How Jonasak stole Penicillin from the giant, Monsanto, and how Jonasak convinced the giant that they didn’t have it by not using it only when the giant had wandered off; because whenever Jonasak used Penicillin, Monsanto would smell and come hunting, and when the giant came closer, people would get sick. We write the story of how the Right Brothers built kites big enough to hang from, and so they won the Air War, and now we can build them from bamboo bones and fabric from its fibers.

And we teach them our migratory route that takes us to the Abani Convention, where we teach each other what we have learned this year, and all rivalries must rest or be resolved. And how to teach and marry into the tribes we meet and pledge to raise our children the Libarrian way: We meet with the Surfers who ride the waves on outriggers and know every rock and where the squid go before Hurricane Season, and how to sail upstream and into the wind to take refuge up Conetakut. And we meet with the Vadailans who know the ways of shellfish, their meat and their shells that they carve into beautiful shapes admired by all; and the Hoarder Peoples, who spring up when a year has been bad, rising like toothgrass from the sand when a year has been bad, as though their seeds had been buried there all along.

And we teach our children the secret languages of the Vulture Priests so the generations-long embers of the Excess and the Contraction don’t burn the children of our great grandchildren, and we teach them to copy even the texts we don’t understand so that someday our descendants may come to understand them.