You know what was great about Firefly? The characters’ interactions were subtle and their motivations, while hidden to themselves, were often clear to everyone else on the ship. Fundamentally, it was a character drama that used a smuggling mcguffin every week to show something about the characters and their relationships.

Now, consider this article over at Wired Magazine that foretells of a Firefly MMORPG. Ignore the fact that he calls Firefly hard science fiction for a moment (Sorry, I can’t ignore it. It’s just… like, neither the author or his editor know what it is? It’s about as hard sci fi as Star Wars, which is about as hard sci fi as Hello Kitty. It’s a literary genre. You’d think an editor would know what it is.) and consider what MMORPGs are good at:

In World of Warcraft, you team up with other players to accomplish quests. Even on designated “role playing” servers, I’m told that the character stuff is pretty thin; it’s a strategy and tactical game (which can still be an RPG, of course). People have fun playing it when they play it as such. The rules don’t support playing a character with motivations and relationships.

Now consider this:

What made the show special was the wry, often self-deprecating humor of its characters, from the captain with the checkered past to the unwittingly sexy engineer, the dull hunk of a mercenary with a girl’s name, and the mysterious young woman passenger with special gifts.

Sounding pretty good, right? (I mean, aside from the fact that Kaylee is wittingly sexy.)

The online version will move away from those central characters — after all, there’s only one Mal Reynolds. In an MMORPG, “everybody has to have their own story,” says Multiverse co-founder and executive producer Corey Bridges.

Now, moving away from those characters, that’s great. Making it so everyone has their own story — their own checkered past, embarrassing name, secret love, death wish, quest for forgiveness or whatever, that’s great. But a shadow falls:

“Television series can be really good properties to turn into MMOs, because when you make a TV series, not only do you need great characters, but you need to create a full, rich, compelling place,” Bridges says. “If you’re doing science fiction, you have to really think it out and create an incredibly rich environment that is compelling in its own right, and worth exploring and going back to week after week. That’s what Joss Whedon did with Firefly.”

See, cuz, no, he didn’t. He didn’t care about how fast the ship could fly, what planets existed, or how ranks work in the Alliance forces. What mattered was that the ship broke to put the characters in conflict with each other, the Confeds were bureaucratic and cold, and that the planets they landed on were stuffed full of characters who wanted something from the protagonists. Shit, he didn’t even know what was on the left side of the bridge until Serenity. He certainly didn’t have a list of planets, ships for sale, and damage values for different weapons.

“We want to find someone who wants to do something unique and fun and interesting, not just a re-skin of World of Warcraft or Star Wars Galaxies,” Bridges says.

Because the underlying technology is already in place, “I feel confident that we’ll see something the public can play sometime in 2008,” he adds.

That underlying technology had better make some leaps and bounds if this is to be anything but a pale shadow of something really fun and engaging.

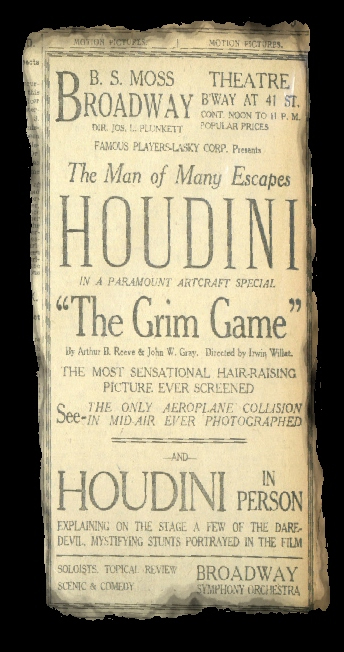

PS: What’s up with the baggy drawers on the dude at the head of this post? He’s a superhero from 1940. He seems to be hiding not only an enormous schlong, but love handles, as well.

I had a little discussion with my friend Kevin a while back on Livejournal about the place that “challenge” has in role-playing games, story games, and the like. It’s a discussion that comes up a fair amount, and Nathan took a good stab at it. I’d like to make some parallel coments.

This article grew out of that discussion. In it, he said that he was rummaging around the D&D 3.5 books to see if they still even talk about “roleplaying”. They do, a little. I challenged him that roleplaying (defined by another friend on his Lj as “giving your character a personality”) was contrary to the rules of D&D, and that you don’t need two big, hardbound books to tell you to use GM fiat for that stuff. But there are games that concentrate on that stuff, like Dogs and PTA.

He said,

But with Dogs in the Vineyard, I felt the same squishiness [as I felt in PTA]. Arbitrary amount of equipment + dice for all of it = bring in a truckload of equipment, then concoct hare-brained uses for it in-game. Better dice for big things = everything big. Add two together = my character’s Big 2d6 Hair. It still felt like the only thing holding back my character was me.

This is the perfect example of this kind of thing. See, it’s hard to find equipment that works in social situations in Dogs, plus guns automatically give you an extra die. But! Those things Kevin mentioned aren’t solutions… they’re bait! You’ve got a little girl who won’t take you to see her brother, who you know is doing grievous wrong and he’s gonna kill someone if you don’t find him. You gonna shoot her?

Let’s make some hypothetical games!

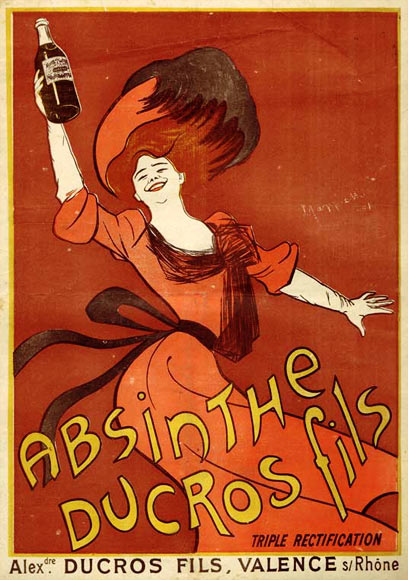

Now, let’s consider the picture at the top of this post. This is a bunch of people who traveled to the North Pole. Now, imagine a couple of ways of making a game about that situation.

1: Will they survive? In this game, we’ve got a couple of different things in opposition to us. There’s the cold, there are polar bears, and there’s a diminishing storage of supplies. These are inputs into the challenge of survival. Maybe we’ve got a list of things that can go wrong and it’s one player’s job to make life really hard, but we guarantee that the explorers can get to the North Pole and back to tell the tale. The game is played by husbanding supplies, taking risks, and planning properly.

When the supplies run out, all members of the expedition who haven’t already died, die. If they survive the experience, they get rewards. Let’s say those turn back around, so next time they’re more likely to succeed. So they have a reason to call it quits, count their blessings on their seven remaining fingers, and try again next year (which is, to say, next week on Game Night).

In summary, our goal here is to properly manage our supplies so that we can deal with the unexpected in the form of challenges made up by another player, likely a GM figure.

2: What will they do to survive? This is a different game, though the situation is the same:a bunch of explorers are going to the North Pole, but our resources, rather than representing your sleeping bags and Power Bars, are the psychological characteristics of the protagonists. In this game, you don’t win by surviving. You win by accomplishing goals you’ve set out for your character: “I want Julie to fall in love with me.” or “I want to kill Bill, that motherfucker, for Julie loving him.”

Perhaps we can even posit that we know that the party will not survive. This will end in snow blindness, murder, and cannibalism.

Furthermore, when your character dies, you don’t lose your ability to affect the story: the more you’ve affected other characters, the more say you have in what they do. Maybe you put this idea in their heads about eating Dave because he’s weak and fatty and holding us back, and they killed you for it… but you can have these dice to roll if you eat my corpse. And if you ate mine, what’s the objection to eating Dave?

In summary, our goal here is to follow up on stuff we care about as people. Moral stuff, emotional stuff.

Let’s compare.

The fictional events of these two games might wind up being exactly the same. That’s entirely possible. What’s different is the intention the players have when sitting down and whether they can use the rules of these games to get what they want. A lot of people might enjoy playing both games. I would. But here’s the thing: you can’t do both at once. If I’m playing to survive, get experience, and try again next time, and your character’s going apeshit and fucking my girlfriend and hitting me on the head with a rock while I’m sleeping and trying to eat my buddy, I’m gonna be annoyed. It’s going to be, why… it’ll be like we’re playing different games!

Likewise, if I’m thinking about our relationship, and putting dice into “You don’t deserve Julie” and you’re not giving me the opposition I need, I’ll be similarly peeved. Cuz you’re thinking, “I’m already carrying 78 pounds of gear (and suffering a -3 to all rolls because of it), and Joshua’s character has to carry the tent and 2 pounds of food, so I’m not gonna engage with his crazy shit.”

At the Forge, we call these Creative Agendas and there are three of them. These two that I’ve mentioned are called Gamism and Narrativism. The third is called Simulationism and has to do with replicating Buffy or Star Wars or My Big Binder of Fantasy Stuff in play. The reason these have been identified is because these are the things that someone wants out of play in a given game. They are not identities: I love playing Agon (which supports Gamist play) and I love playing Shock: (which supports Narrativist play). These are things I like, but they are not things that I am.

So when I sit down to play a game, I don’t want any mystery about what Agenda is being supported. D&D, GURPS, Cyberpunk, Agon, and even Fudge, don’t support a Narrativist agenda, so I don’t want to address theme while I’m playing those games. I want clear rules where the clever application of them is rewarded. Likewise, I don’t look to Dogs in the Vineyard, Prime Time Adventures, Shock:, or Breaking the Ice to prove to myself and my friends how awesome I am strategically and tactically. There may be shared elements, to be sure: a sympathetic character in a game of Agon, or figuring out how to get as many dice as I can on the table in Dogs. But these are techniques used to make play move on a moment-to-moment basis. They don’t address my Agenda at the time.

What does this mean for this week’s game?

Talk with your players and figure out what they want. Do you want character drama? That means the players are working with a Narrativist agenda this week. Does one guy want to explore a hero’s youth and what made him become a hero, but everyone else wants to slay dragons, already? It looks like you’ve got two separate potential agendas here. Maybe this week we’re playing Agon and next week we’re playing Hero’s Banner. But don’t make that guy try to tell his story by using combat rules, and don’t make everyone else play out a teenage drama when they want to be one-upping each other in bloody asskickedness. For Jebus’ sake, play different games. Don’t shoehorn one into the other. Here, I’ll say it again in its own paragraph:

Don’t use a system that doesn’t support the creative agenda of the players. Those players are flexible people; they like lots of different things. Discuss it, agree on something (and probably agree to play something else next), and play the game that does what you want to do tonight.