This story is thinly veiled personal experience, pointing toward my desire to make an adventure roleplaying game about being an interdimensional experimental musician with a cool warehouse studio who gets to hang out with your favorite real world musicians. Are there enough experimental music enthusiasts to get a group together? Who knows! There are a couple of my Discord, so when this game starts to gel I should make sure that the kind of experience I’m describing here works well remotely.

But also, this story is as personal as it is silly.

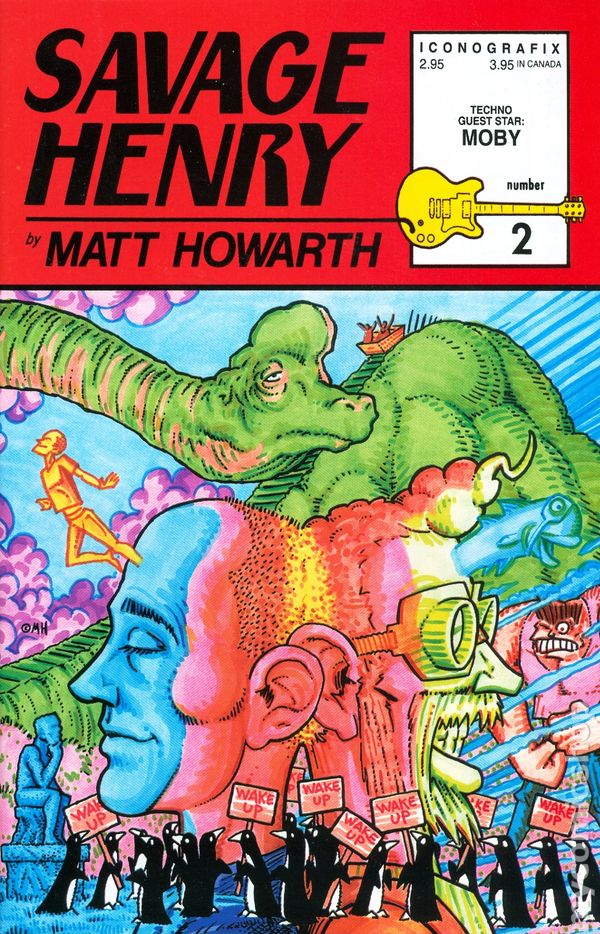

(The image at the top is a cover of Savage Henry, a comic about just such weirdo musicians. The series and its creator, Matt Howarth, have been an inspiration to me for thirty years.)

You put on the headphones. They’re your favorite kind, though they do get hot in the summer. You had to repair them once, and you lost one of the screws, so you stuck the case back together with a sticker from your friends’ band. You call them your Robokitty headphones now, instead of the company that made them. Something changed when you put the sticker on. They sound better. You bought them all those years ago because the frequency response is deliciously flat, faithfully reporting to your sensorium the signals you generate. But now, with the Robokitty sticker, they somehow sound even better, like there’s another kind of meaning in the sound you couldn’t hear before you’d lost that screw and decided on the sticker solution.

You click their curly cord into one of the dozen jacks on a repurposed ammo box and are relieved that you hear nothing. No 60Hz hum of the electrical grid like last week, even though when you’d tried to fix it, you’d wound up with everything plugged in the same way it had been before, only quiet. And now, just silence. You trust the cans on your ears: silence is what your creation is making. It is waiting to begin the dream that you will take part in, meshing your mind with the self-revealing, emerging structures of the singing, improvising circuit in harmony with your central nervous system in conversation with the circuit, a living thing, a person with thoughts outside their body.

You reach into the canvas, store-brand shopping bag at your side, filled with tangles of wires that twist together like the folds of a brain, and draw one out. It’s in an incidental knot with another and they come out together in your hand. You click the first wire into the ammo box’s square wave oscillator, generating a pulse like half a heartbeat, to the trigger of the Sample & Hold; then you connect the other between a slow sine wave, slow like a breath, into the Sample & Hold input. The silence in your ears becomes pregnant.

Your hand follows your intuition and you dip your hand back into the canvas bag to draw out a handful of cables, connecting a trumpet-like sawtooth wave to a filter, asking the first part of the question. Your hands deftly connect the output of the Sample and Hold to the filter’s audio input as the second part of the question you’re posing. You connect the output of the filter to the amplifier, completing the circuit to the headphones, the headphones to your ears, your ears to your mind, your mind to your hands, and with that, you complete the loop. The machine gains your human intuition and you become part of the machine.

The sawtooth sounds momentarily like a trumpet, but the filter softens it, highlighting sounds like distant flutes that come into and out of existence like notes played on the metronome of meditating breath.

You repeat the experiment, varying one variable: another slow breathing sine wave connects to filter out the lowest frequencies. The trumpets that become flutes are joined by the chirps and clicks of dolphins and perhaps birds, but more likely something like both of them. Something that does not exist in our world.

One by one, you pile oscillations onto each other, finding timbres that have never before existed on Earth, making tiny folds in the sounds, inspiring new exploration, finding new life forms to hear, rushing krinkling cataracts of frozen methane and thunderous rapids of molten lead lapping on shores of iron.

In it, you hear voices passing by, as though tuning a shortwave radio across the world in the middle of the night, like you used to do on your boom box. And like with that radio, turning the knob back doesn’t reveal the voice again. Your eyes are closed, your finger applying gentle pressure to the knob, moving it imperceptable fractions of a degree, trying to find that harmonic that sounded like it was speaking, telling you about something, but the harmonic has passed.

You plug in another oscillator to the breathing sine wave to vary its frequency very slightly, setting off a flutter of changes in every filter, every oscillation, every click of the clock. You try to estimate the time before this sound repeats itself. Hundreds of hours before the themes would again rejoin in this way?

You sit back and listen. It fills your mind and you see the structure of the sound. Little animals scurrying on land that emerges as the back of a gargantuan being, sapient and slow beyond your understanding. Mountains rise and are ground down by rivers. Seas dry and are refilled as continents move.

And there is the voice again, first broken up in flutters like cards in the spokes of a bicycle, speaking, almost perceptible. Almost familiar. The spokes get closer, become words, inviting you. It has been trying to reach you, it says. You can help. You can leave the world and return to it changed, to change the world and make it better.

The fundamental frequency of your voice is 228 Hz, it says. You look at the oscilloscope, currently showing a histogram. The fundamental frequency of this signal is 228Hz. The voice you are hearing is your own.

“Tune it,” the voice says, “To make yourself what you need to be.”

The voice is still coarse and distant, emerging from washes of chirps and rumbles. It makes affirming sounds as your hands gently touch the oscillators and the filters. You listen as you adjust their parameters and adjust parameters according to their sounds, making decisions on unknown criteria until the voice is lucid. It is your voice, but it does not sound like you. Your eyes are open, but the studio, with its coffee cups and old computer monitors, half-built keyboards and bird skeletons, is gone, is different, the vibrations from the Robokitty headphones squeezing you like toothpaste, and like toothpaste you feel no pressure — instead, you slide, ooze out the side.

Your ammo box synthesizer is here with you, but the studio is no longer the one you were in, though it is yours. The lighting is good. You are standing at a table the right height. The walls are brick, painted white. High on the walls are windows, through which you can see the sky blue pink light of the rising sun.

You are home here, and you are you — more you than you’ve been before. Your hands are as you envision them, graceful but strong. Your face feels like it does when you imagine it, rather than what you see in the mirror.

“Thank you for joining me,” your voice, though you didn’t speak. You turn toward the source that still krinkles with the sound of methane waterfalls shudders with the sound of lead on iron shores in your headphones.