This post took a lot of writing and drawing! Help me make more good stuff by backing xenoglyph on Patreon!

I’m a big fan of science fiction. I’m also a big Star Wars fan. I think, though am not sure, that my first movie was Star Wars, which came out four days after my fourth birthday. I’d guess that 2001 was my second.

Even as a kid, I could tell that these were not the same thing. They each had their own aesthetic principles that, if I was to play with the ideas in them, I would have to derive and distill, but not mistake for one another.

Sitting in the theater, watching 2001 with my hands over my ears, my eyes alternately staring in hypnotized wonder and closing with overwhelm, I felt like Kubrick has said he wanted the audience to feel: like the universe is vast and, though it has a coherence, it was not something we were ready to understand. As time has gone on, I recognize this (rare) kind of science fiction as being about finding out what we humans are capable of.

On the other hand, sitting in the theater with my dad, who had just returned from seeing Star Wars that same afternoon to see if it was appropriate for me, I saw a world of heroes who built and drove machines and thrived on their knowledge, kindness, courage, and beauty. I didn’t understand for years that there was even a plot to Star Wars at all; that it wasn’t all simply imaginary material to play with. It was like intellectual LEGO to me (which I would only encounter for the first time a year or so later as a somewhat obscure Danish toy my Montessori teacher aunt bought for me for Chanukah) — to “play Star Wars” was to share in the imagination of daring acts of flying, shooting, rescuing, and blowing stuff up. As an adult, I’ve come to recognize that Star Wars (and its rare competent knockoffs and antecedents) are about romantic hope, about our realization of our core nature that, we could once access, but have since lost contact with.

Guess which one I found my friends more willing to play make-believe about.

Star Wars, as Lucas has bragged for decades now, is made of the familiar. He talks about his (clearly retrofit) Campbellian Hero’s Journey themes. He talk about WWII dogfights and battleships. He talks about hot rods.

And he never talks about the future.

In 1968, “The Year 2001” was the distant future. Clarke and Kubrick were each concerned with nuclear annihilation, but Clarke, for one, was not overly interested in the systemic causes of it: the empire that he benefitted from had placed him comfortably at his home in Sri Lanka. He wanted a future in which humans obliterated their differences, like forward-thinking Englishmen have tended to wish.

Stanley Kubrick, I have to imagine, knew he was cutting against the grain, placing a cadre of white American men as our feeble representatives to the galactic community; that they lived a life of self-delusion about their greatness, but had wound up wielding the power of the planet due to a series of historical accidents and, for better or worse, it was a lone representative of that history who made first contact — but aided by the power of Earth’s posthuman future in the form of HAL and Discovery 1.

On my first birthday, Lucas completed the first draft of his Kurosawa/Flash Gordon pastiche. He declined to place it in a future at all, but instead cloaked it in Tolkeinian archaism of kingdoms and knights and dying sacred orders.

It is that romance — that conservatism, that longing for the imagined past — that defines Star Wars. And that conservatism was finally, skillfully challenged for the first time in The Last Jedi.

From our perspective, from 1977 through December 2017, though, the magic Star Wars combination seems to come from a synthesis of two perspectives on the past: the pre-industrial past and the industrial past.

The pre-industrial past is one of shamans, samurai, sacred bloodlines, trial by ordeal, distinguishing oneself through acts of bravery and violence, handcrafted objects of unique qualities, casually accepted slavery, and an inexplicable and willful universe.

The industrial past is the past admired by the American Boomer generation, whose parents sacrificed everything, only to reward their children for decades with the accumulating, extracted value of the world. It is a past of sheet metal, mass production, turbines and pistons, hot rodding juvenile delinquents, allied democracies, medical marvels, alienation from the forces of nature, genocide, weapons of mass destruction, blitzkreig vs. partisans, and gunslinging individualism.

The closest any given Star Wars thing can come to addressing the present is when it faces our least-current-yet-still-relevant concerns: empire and its military oppression; mechanisms of dehumanization; families in flux; alienation from nature.

“Alienation from nature” has a particularly prominent position in Star Wars. It’s represented through the use of prosthetics, like Luke’s hand and Lobot’s, ah…hairstyle? Vader’s “More machine than man” nature is touted as his alienation from all that is good in the universe, but, in addition to the very questionable and aggressively ablist perspective that it comes from (no one I’ve met with prostheses or wheelchairs seems any less in touch with the world to me) you could also look at it as a question: “When your symmetry is violated, do you view it as a deep scar on your crude matter, or do you allow your luminous being to shine through?”

In a maximally charitable reading, I think that’s the core question of the series, and when a Star Wars story wanders afield from it, it literally starts to lose its soul. It can’t really address the soft empires of financial and trade networks (demonstrably, in fact), or information warfare beyond coarse propaganda, and it certainly can’t handle the subtlety of automation obsolescing humans or drone warfare without defying its metaphor of droids-as-enslaved-people. It can’t even handle the existence of software.

But, because it’s our syncretic, American mythology, it still requires a system of thought. And because it’s a mythology, it evolves.

Most of xenoglyph is dedicated to 2001-inspired imagination.

This time, let’s make up a Star Wars guy.

You might use this same process for a city or a spaceship, but we’ll use it right now for a character for a roleplaying game, or for fanfic, or whatever. I’m going to choose according to my own aesthetic inclinations, of course, but I invite you to use this process with your own.

Here’s the process we’re gonna use here:

1. Pick some pre-industrial elements.

2. Pick some industrial elements.

3. Pick a Modern (not Postmodern!) concern the character has.

4. Let each of these inform another, either directly or ironically.

5. Don’t forget that people in Star Wars have families.

Oota Toota, Ashadd Nash?

Let’s make a smuggler, sneaking goods to the Rebellion, running Imperial blockades. Their Modern concern is that their quest for freedom has turned into a quest for money.

Let’s give them some of their cultural elements:

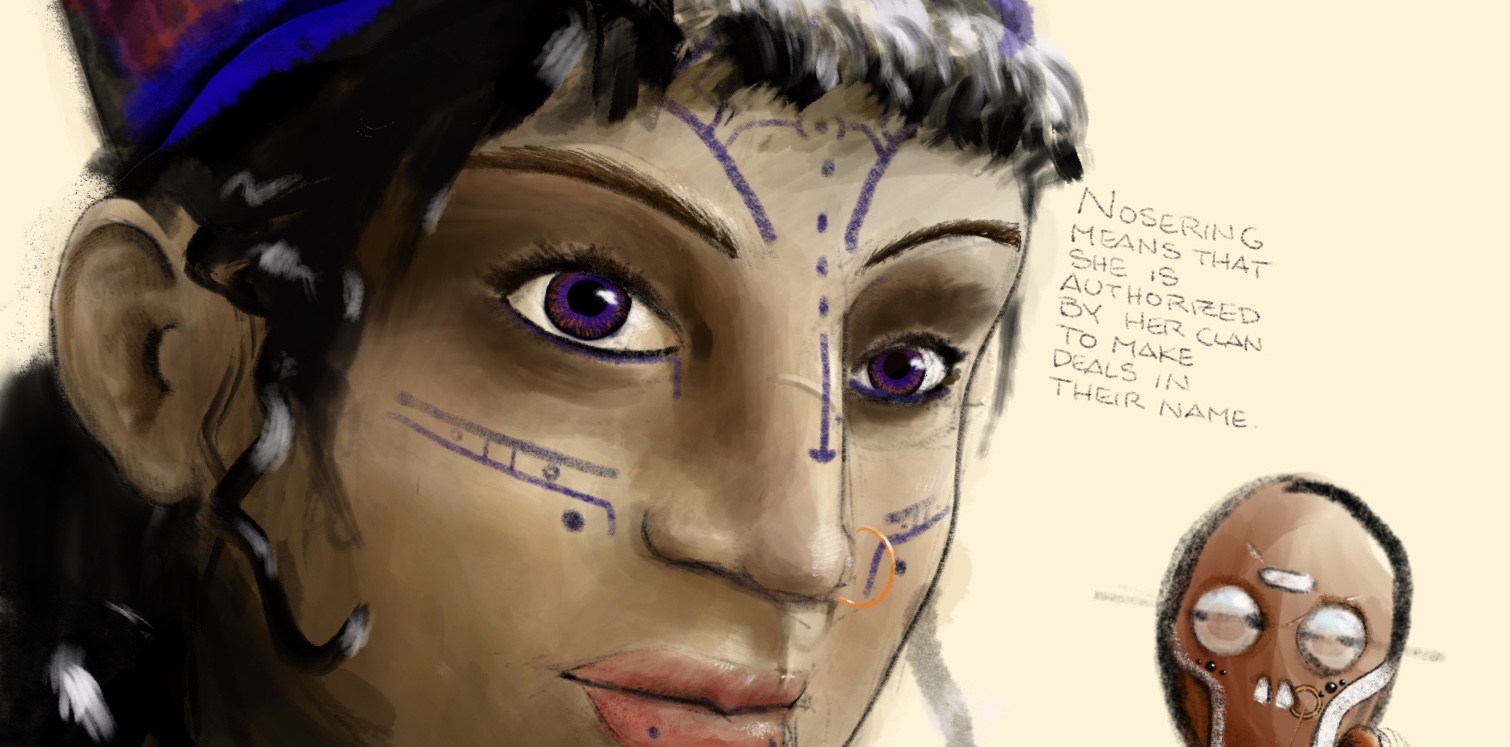

- Following the third trilogy’s quest to remind us of the existence of nonwhite, nondude protagonists, this is gonna be a woman. Her face is detailed in tattoos.

- She’s inspired by Bedouin and Touareg nomads.

Then let’s put some Industrial Age twists on her culture:

- These tattoos are echoed on her environment mask and serve a couple of functions. One of them is that the mask can see in infrared and help her figure out when a fellow scoundrel (or, more likely, someone who considers themselves more civilized than her) is lying to her. Big help in the business. They also work as macrobinoculars and microscopes, helping her appraise the weapons and goods she smuggles.

Now, back to the pre-industrial elements:

- Her people’s tattoos also concentrate one’s connection to The Force. It’s not just the sensors on her enviro mask that tell her when someone’s lying; she’s unusually perceptive without them, as well. And others tend to do what she says, even if later they don’t remember why they thought it was such a good idea at the time.

Add an Industrial Age element:

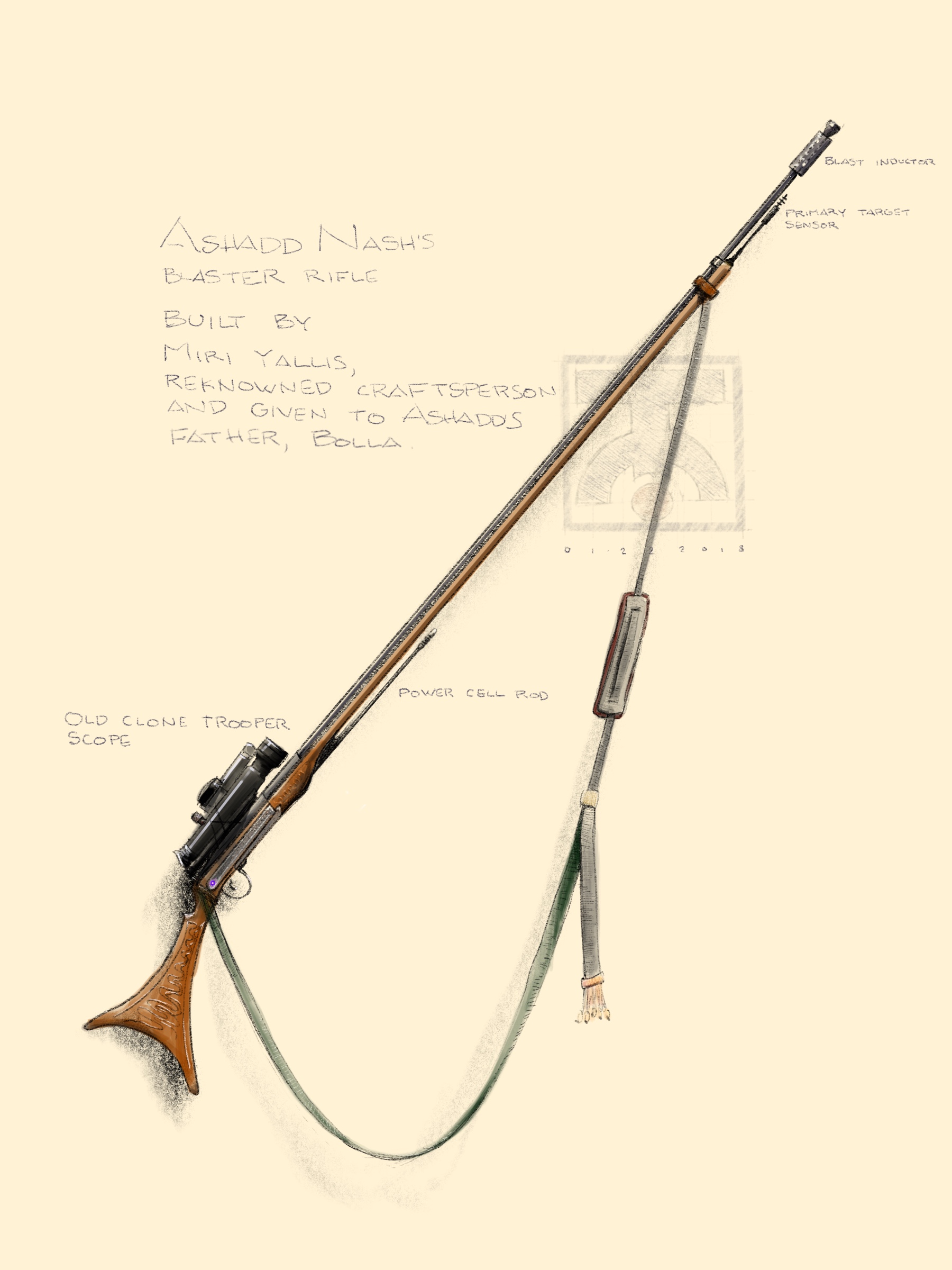

- She carries a long blaster rifle, great for solving scoundrel problems at a distance.

And let’s make it pre-industrial

- It has the flare of an early 20th century Arab rifle. It’s made of wood with inlaid elements that have been replaced with delicate care over time. It’s kept clean and in good repair. We can see some Tusken Raiders using similar weapons, even though those aren’t Ashadd’s people. It’s the kind of weapon you use when you don’t want to miss, and want to make sure no one wants to make you unsling it from your back.

- It’s also pretty good as a club. I bet we can get her doing some newstyle Star Wars wuxia action with that thing.

But we can’t leave her with such an impractical, showy weapon. She’s a businessentity, after all:

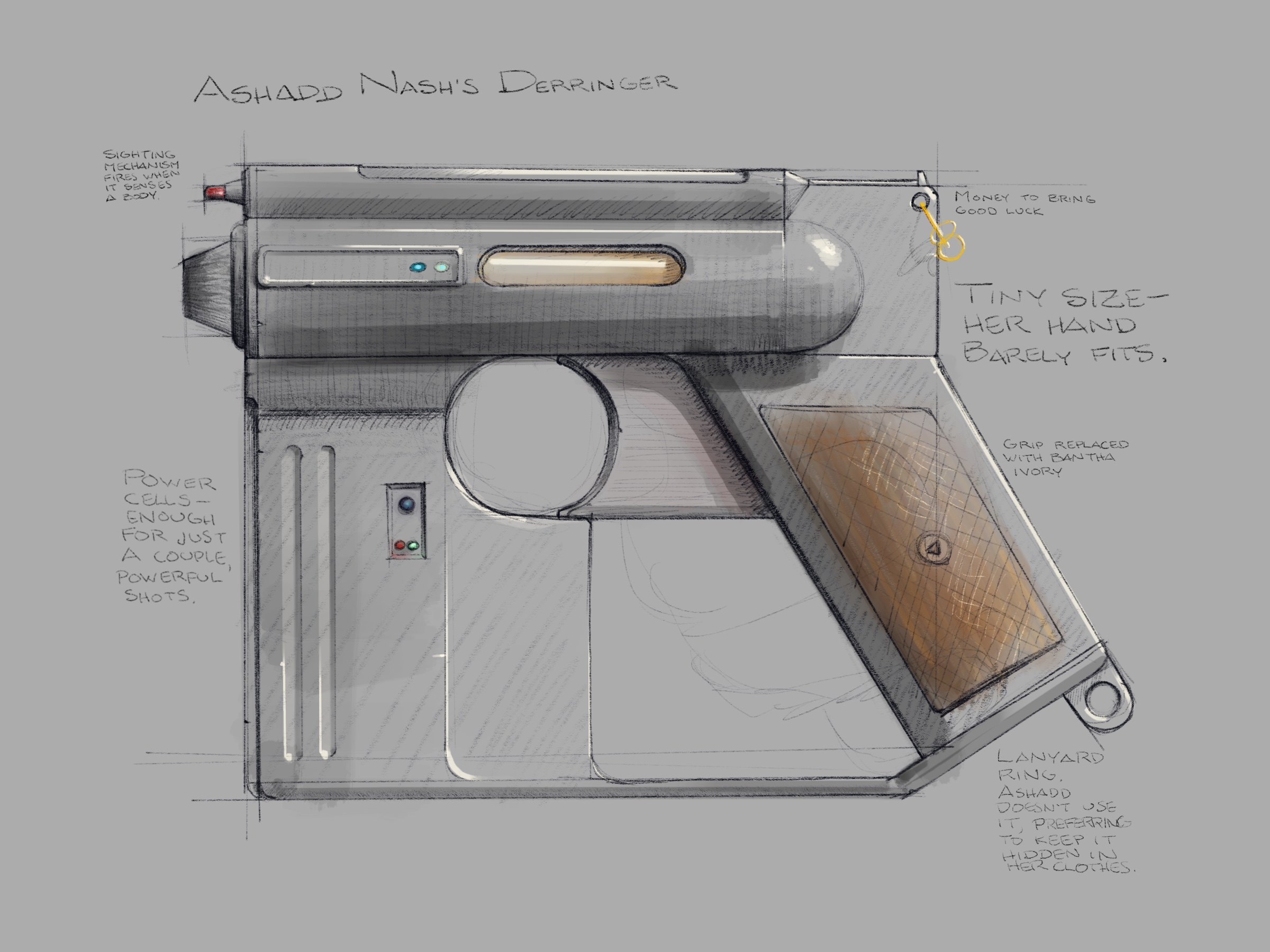

- She also carries a derringer blaster. It’s an ugly little box shape, designed to be carried by Imperial officers, like the one who lost it to her in a game of Sabacc by trying to draw it on her and finding himself unable to aim effectively. Its shapes are drawn from the German MP-40 submachine gun, with some added unnecessary lights. Its overall shape is inspired by the USFA “Zip Gun”, which is a weird, extremely industrial shape. By all accounts, the Zip is a terribly unreliable machine, but obviously guns only jam in Star Wars when it might be dramatically important, anyway.

…nor can we leave her without her cultural elements.

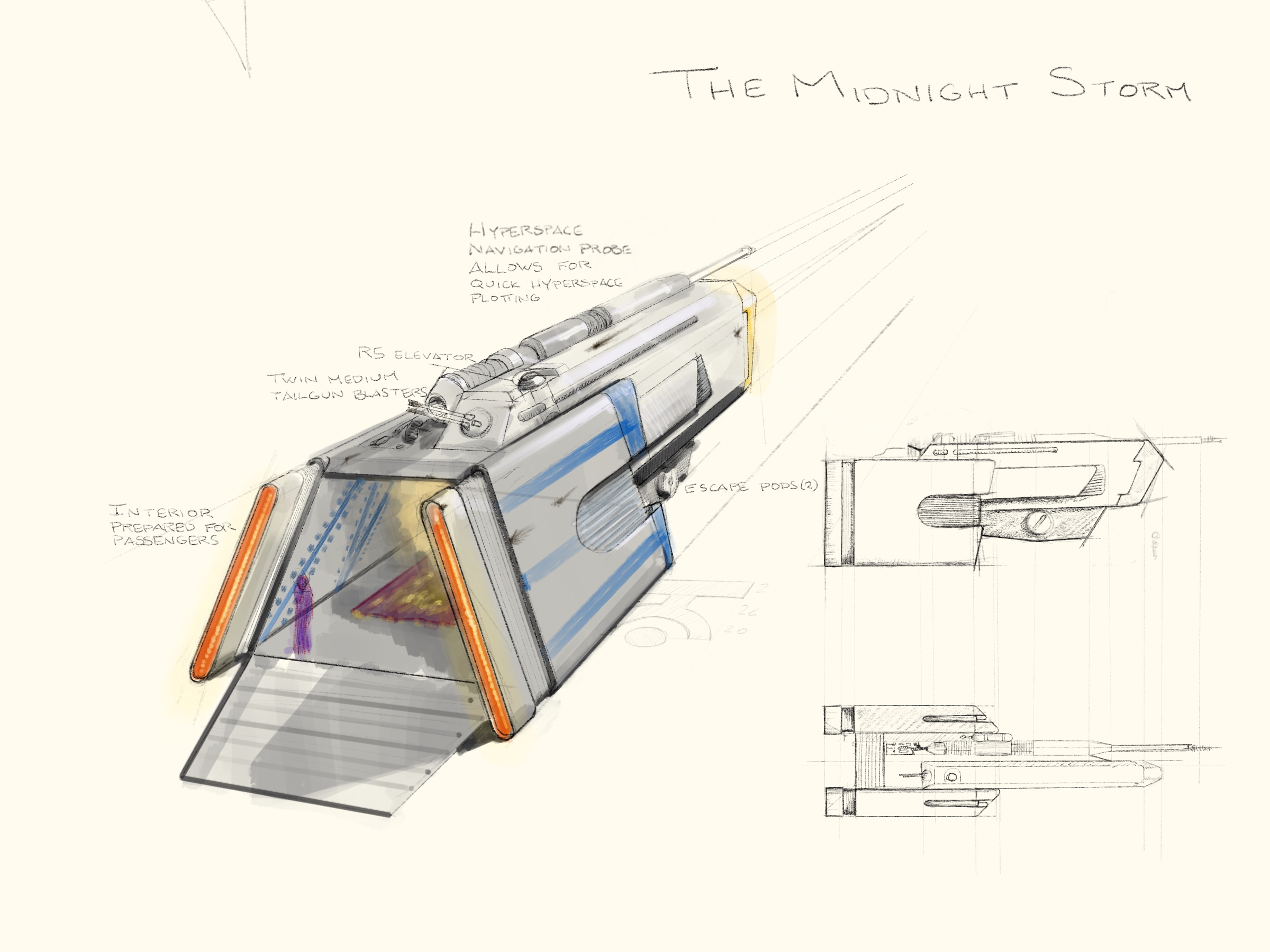

- Her ship, the Midnight Storm, is outfitted to display her wealth. It’s carpeted, fer fucksake. Hanging from the ceiling are strings of coins from every system you’ve ever heard of, and lots you haven’t. The walls of the cabins are painted in zigzag patterns.

…But, of course, it’s a practical, mechanical device, originally mass-produced.

- The cockpit is a tight fit for three, with room for a pilot, copilot, and a jump seat where R5-M5 astromech droid usually plugs in. R5 can take an elevator to the roof, if needs be.

- There’s enough room for a bunch of crates of weapons (some hidden) and a handful of passengers. More passengers than that, if they don’t mind sleeping on the floor.

What She Wants

Ashadd’s people usually travel in caravans from system to system, trading at one spaceport, meeting and trading with a cousin caravan at another. But when her caravan was framed for piracy against an Imperial convoy by a former ally, the Empire took an interest in her caravan and pursued them. The caravan’s families in their ships scattered across the sector, and bounties have been put on their heads.

Upon finding her uncle Ashadd Burdo in the custody of the bounty hunter Raag Ulesh, she paid Ulesh the bounty herself (with a keep-quiet bonus), then snuck her uncle to Kasho Spaceport, where he now lives a hidden life as part of the market there, acting as Ashadd’s fixer. Her relationship with Raag is now somewhere between collegial and tense. They both expect the other to betray them as soon as the relationship becomes less profitable.

Ashadd now lives to gain the money to find the rest of her family, but the bounties on their heads keep growing as Imperial Inspector Goruss feels the pressure to secure the sector from pirates. Ashadd keeps accumulating cash, the bounties keep getting higher, and as she gets richer, she finds it harder and harder to feel the presence of her family across space. With each smuggling job, she accumulates more money to pay bounty hunters to find them for her — bounty hunters who know they’ll have a competing bid if they take their quarry toward the Empire first.

This post took a lot of writing and drawing! Help me make more good stuff by backing xenoglyph on Patreon!

I’d love to see who you meet and where you go as you travel across the Galaxy!

This is awesome, Joshua!

Huhhhh. Your method sure is intriguing! I’ll have to give that a try some time, splitting the source material into themes, and building that into *every* step of the process…

Thank you! For a rather surprising number of years, I’ve been thinking about what makes Star Wars so Star Warsical, and this is where I got to!