I often talk about the future, thanks to Alvin Toffler, as a shockwave. I have to figure out how to face that wave every day. If I’m too far out in front of it, the best I can hope for is to be posthumously recognized as a person ahead of their time. Alan Turing was such a man, tortured to suicide by the government and country that he saved, for the homosexual proclivities that his country’s enemies had vowed to eradicate. And here I am, typing in a café on a Turing Machine the size of a single information theory paper written by Turing. Even worse, I don’t have the intelligence, talent, or clarity of thought that Turing had. So the best I can hope for is to be a third-rate Manfred Macx. And he’s not even real.

Another danger is to try to live on the crest of the wave. But it’s crowded with the cowardly investors of Wall Street, who recognize when risk has been carefully polished out of a system by the hard work of creators and laborers, then extract its benefits at minimal cost. These are also consumers, who choose from available, low-cost products and services. They benefit from shaken-out designs, mass production, and the low costs associated with both. The particular goods eventually fail (through wear or obsolescence), and they discard them for new ones. They don’t feel the need to understand the materials of their lives; they’ve been driven into a panic by the value-extractors taking all the space at the top of the wave, and so don’t have the time to self educate. Eventually, though, propelled up faster than they can move forward, they fall into the churn behind the shockwave with a collective cry of “I don’t understand Dubstep!“.

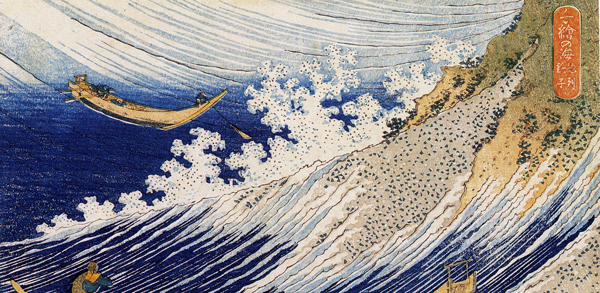

But the rising wave. Ahh, the rising wave. That’s the slope lift that carries gulls in that skating, sideways motion at the shore and, facing them, is the curl ridden by surfers.*

Both find the unstable quiet point where they balance the forces that make them fall (gravity, in the real world) and those that make them rise (the sea breeze rising against the dunes in the case of the seagulls riding the wind, and the wave rising up as the ocean folds up upon contact with the beach in the case of the surfers). To those standing on the beach, they give the illusion of stability, but what they have is precisely the instability they require to move forward at the rate of change. Dive too fast, and get hit by the curl, winding up like Turing. Get conservative, and you wind up a consumer or a value-extractor falling behind. This is the sweet spot where sociotechnological future-surfing takes place. This is where it’s worth experimenting with a new medium, where the early adopters squeeze what they can out of social networking; out of cheap, precise light sensors; out of microprocessors, out of cameræ obscuræ and curved mirrors, out of cat jokes and experimental educational techniques. If someone is worth reading about, they are (or were) one of these surfers. They know they’ll fall eventually, to get tumbled and crushed by the wave like everyone else. But that’s only once they fall due to inflexibility. To stay on the rising curve, they do more than learn about new stuff: they learn how to learn about new stuff. It’s that learning about learning that they use to paddle to speed with the wave, stand, and hang ten.

Such a process of autodidacticism is deeply, corrosively antithetical to most modern systems of education, formed to create a population of moral factory workers (factory work being considered optimally moral and only coincidentally beneficial to factory owners). The Calvinism that forms the moral basis of so much US culture holds that curiosity, sexuality, and creativity make one into a cultural liability; and yet, we admire so greatly the oddballs who shake Calvin’s grim shackles because they’re an expression of raw, uncontrollable, improbably (we’re told) self-focused humanity.

But Lord of the Flies is the result of the children’s education, not the absence of teachers.

I think we can largely agree that Isaac Asimov was a pretty smart guy. Let’s see what he suggests.

What he describes there should be obvious, if not downright familiar, to all of us now. This is just what we just do at our moment in history. We want to know how to do something and we look it up. Sometimes, we get really into it. We literally become smarter, integrating the metacortex of search engines and our shared knowledge into our everyday cognitive processes. I might no longer remember all my friends’ phone numbers, but I can see the edge of the Universe, talk with delightful Italians, and see the single funniest animation of a cat falling in the tub at the flick of a finger. Siri, what’s my sister’s phone number?

In the process of making this possible, a qualitative change has taken place. For the last century, the Second Wave (for our purposes, and those of Toffler, the first to experience society-altering industrial sociotechnological change) has dumped its waste on the First Wave (agricultural) parts of the world. It’s been carcinogens and lead, mercury and diazanon. But as the wave of change has passed into Third Wave information technologies, our waste — that is, products almost too cheap to sell — have gone from 20th century toxins to data storage, processing, and communication.

Our waste is smart.

That means that, not only is One Laptop Per Child possible, but we humans get to simply end-run the Third Wave societies’ struggle to hatch information technologies. It’s costly to send copper cable to Kenya. It’s heavy and valuable, so it can get stolen in the vast distances it has to cover. But cell phone antennae are central and easy to defend. You can charge a phone with so little electricity, you can generate it by stepping on a treadle. And so, the Internet, seeing that market failure as damage, routed around the limits of landline infrastructure, right into the pockets of African people.

And you see the factories churning out tablets and iPhones copied by Shanzhai designers, lashing local designers’ own knowledge and needs to the technologies they’re producing in their day jobs. It’s not Designed in Cupertino, California, but Cupertino induces Shanzhai like magnets induce electricity. You can’t make something without inducing others to make something reacting to the creation. This process seems to be a natural process, the consequence of creation, focused where the manufacturing happens. Now imagine what happens when your 3D printer can print not only shoes, not only food, but more 3D printers. And every basement, bedroom, classroom, community center, library, improvised hovel, and pocket has one, interacting in creative induction.

The most important part of this process to me is that it’s returning, if accidentally and contrary to the wishes of the traditional benefactors, some of the value the now-Third Wave nations have captured from the rest of the world during its brutal rise. First, we returned resources that we’d refined into toxins, and until we change some things, we will continue accruing that karma. But with the toxins now comes something so cheap, you can barely sell it at all: Information. And kids will absorb it as readily as they absorb lead, mercury, and arsenic. Contrary to what John Calvin and his centuries of dominance-obsessed paternalists preferred to think, people like to learn, to get better at things, to feel compassion for each other, and to share. Of course, Calvin, who considered wealth to be evidence of God’s grace upon those who (surely must) have worked hard, made a fine model for those who wished to demonstrate their moral rectitude by simply having possessions while giving others plenty of opportunity to work. So when you find that kids whose village has never seen a word are able to sing the alphabet and teach it to their parents; or teach themselves how to navigate the Internet and eventually biochemistry; or simply learn math because their teacher was able to read about Sugata Mitra and find himself released from the need to prevent kids from learning what they wanted to learn; we might find hope that our transhuman and posthuman futures are being expressed through the unbridled, wild, profane, hilarious nature of our humanity.

It’s that nature that I expect to break through when India, a country that has illegalized pornography, releases a million Aakash tablets on its population. In the two years since its inception, it has already been through six iterations. New, the tablets cost $50 and the price is expected to drop to $20 as kinks are worked out and production ramps up. They’re going first to colleges, of course, but it’s not like those students aren’t going to want the newest one. That’s a lot of smart waste. And what motivates a student faster than a locked door? A door that might have sex on the other side? Forbiiiiiiden sex?

Those kids, those kids will learn to surf.

*I grew up on an island. All my metaphors are litoral.