Over at Centauri Dreams, there’s an article about seeing alien planets up close, and what would be required. (Emphases mine)

Huge space arrays could help follow up our investigations of such a discovery, but Schneider notes that to get a 100-pixel image of a planet with twice the Earth’s diameter some 16.3 light years away would require the elements of the array to be more than 43 miles apart. Having set up this interferometric system, we could snap images of things like rings, clouds, oceans or continents, and could monitor changes in cloud cover. But we would still be missing something we’d really like to know. Just what do the inhabitants of this place look like?

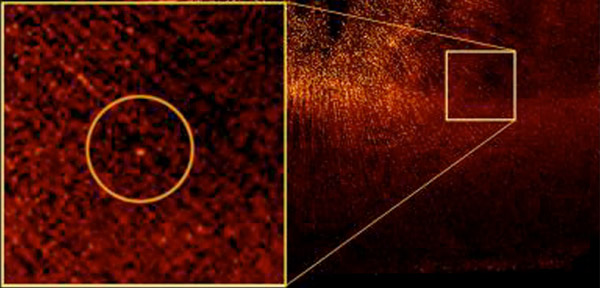

…To begin imaging even giant organisms 30 feet long and wide on the closest putative exoplanet, Alpha Centauri AB b, some 4.37 light years away, the elements making up a telescope array would have to cover a distance roughly 400,000 miles wide, or almost the Sun’s radius. The area required to collect even one photon a year in light reflected off such a planet is some 60 miles wide.

For us, dealing with practical budgets, international ethnic conflicts, and scarcity — both imposed and amoral — those numbers are fantastically out of reach. But for the Academy, they’re not. What is impractical for the Academy is filling the solar system with sensors that get in the way of other sensors. And that means that there’s competition for sensor time, just like at the VLA and the Arecibo telescope. To avoid that, there’s a lot of poring over data that others have collected — evidence that’s compelling enough to invest a singular resource into.

So it seems likely that one of the missions of every starship is to start setting up a new array when they arrive somewhere. The data will either return on a starship or eventually be picked up by an array in some other solar system, probably centuries later.

Keeping in mind that any information so gathered is decades to millennia old, the Academy can watch out for signs of humanity, from agricultural land change to nighttime city lights and expansion to nearby planets. If they’re lucky (?), they might catch images of nuclear explosions or the sparkling of starships.

Keeping in mind that data would be gathered in single photons over years, there would be nothing realtime about it — no radio data (though they could probably confirm the use of radio) and no images of anything that moves erratically. But it’s enough to know that there’s someone there.

That’s really interesting. I’m curious, though…. Are the distances so great in light years that the Colonists wouldn’t have arrived yet?

Well, colonists have been out there for at least tens of thousands of years. There are rather a lot of stars in any given volume of space 20,000 light years across.

No one knows, of course, if there are colonies beyond that radius. Better go to a colony near the edge and set up an array!

Well, if you figure that the Academy’s been around for 800 years, and the colony ships left before that…. So like 1000 light years? 1500? The Orion Nebula is 1500 light years away according to a lazy googling. Is that enough “room” for there to be a bunch of potentially-inhabitable planets?

The Academy’s been around for 800 years, but there’s scattered evidence of exoduses from Earth all the way back 100,000 years.

The Orion Nebula is 24 light years across — it makes stars. It’s a huge structure.

Here’s a list of stars within 16 light years. There are, I guess, some 2000 stars within three times that distance.

Awesome. That means this totally works, and not just through avoiding paying attention.

I’m doing every single piece of research that’s convenient to prove what I want to be true!